Serial entrepreneur Fujimura Tetsu argues that the width and depth of Japanese IP resources make the country an entertainment industry leader.

For the past decade, Korean entertainment has increasingly challenged English-language content for eyeballs, especially within East Asia. Japanese IP may now be emerging as an even larger source of material that is poised to go, not just regional, but global.

Major investment groups like Blackstone and T Rowe Price and multinational entertainment corporations such as Sony, Netflix and Disney have similarly taken notice and are making ever larger financial commitments to the Japanese sector.

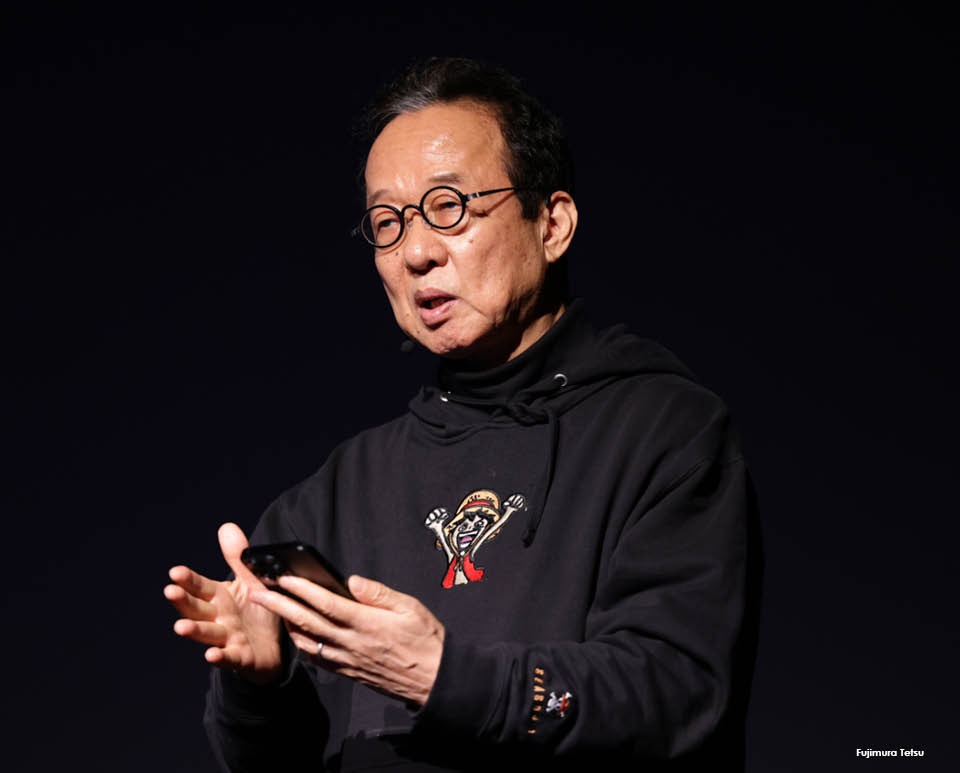

In a 90-minute presentation at the recent TIFFCOM event in Tokyo, serial entrepreneur Fujimura Tetsu, laid out a detailed economic case for this shift and hailed Japanese IP as a “treasure chest” that has a “remarkable future” ahead of it.

Fujimura was formerly the founder of Japanese indie film company Gaga Communications before exiting in a 2004 sale to USEN group. Shortly after, he founded Filosophia as a consultancy and production group that sought to be a bridge between Japan and Hollywood

He credits his understanding of the potential of Japanese IP to two mentors: Avi Arad, the former toy designer who acquired the bankrupt Marvel comics firm, revived it and sold it to Disney for more than 20 times what he paid; and to Martin “Marty” Adelstein, a former screenwriter who became a partner at Endeavor and later founded Tomorrow Studios with ITV. As producers, both focused on high-end projects capable of global impact. That is a focus that Filosophia aims to emulate and to which Fujimura says Japanese IP is especially well suited.

Fujimura is an executive producer on the Netflix-driven live-action adaptation of One Piece, which is heading into a third season.

His thesis is built on the notion that films based on pre-existing IP have grown their share of global box office from 10-20% 45 years ago to nearly 90% today.

That shift favours all IP owners over those struggling to create wholly original works. And it favours Japanese IP owners, in particular, because the country has a “triple whammy” of: i) manga (comics) ii) anime (animated films and TV shows); and iii) i...

Serial entrepreneur Fujimura Tetsu argues that the width and depth of Japanese IP resources make the country an entertainment industry leader.

For the past decade, Korean entertainment has increasingly challenged English-language content for eyeballs, especially within East Asia. Japanese IP may now be emerging as an even larger source of material that is poised to go, not just regional, but global.

Major investment groups like Blackstone and T Rowe Price and multinational entertainment corporations such as Sony, Netflix and Disney have similarly taken notice and are making ever larger financial commitments to the Japanese sector.

In a 90-minute presentation at the recent TIFFCOM event in Tokyo, serial entrepreneur Fujimura Tetsu, laid out a detailed economic case for this shift and hailed Japanese IP as a “treasure chest” that has a “remarkable future” ahead of it.

Fujimura was formerly the founder of Japanese indie film company Gaga Communications before exiting in a 2004 sale to USEN group. Shortly after, he founded Filosophia as a consultancy and production group that sought to be a bridge between Japan and Hollywood

He credits his understanding of the potential of Japanese IP to two mentors: Avi Arad, the former toy designer who acquired the bankrupt Marvel comics firm, revived it and sold it to Disney for more than 20 times what he paid; and to Martin “Marty” Adelstein, a former screenwriter who became a partner at Endeavor and later founded Tomorrow Studios with ITV. As producers, both focused on high-end projects capable of global impact. That is a focus that Filosophia aims to emulate and to which Fujimura says Japanese IP is especially well suited.

Fujimura is an executive producer on the Netflix-driven live-action adaptation of One Piece, which is heading into a third season.

His thesis is built on the notion that films based on pre-existing IP have grown their share of global box office from 10-20% 45 years ago to nearly 90% today.

That shift favours all IP owners over those struggling to create wholly original works. And it favours Japanese IP owners, in particular, because the country has a “triple whammy” of: i) manga (comics) ii) anime (animated films and TV shows); and iii) is a powerhouse of gaming firms dealing in both hardware and software.

Indeed, all of the top 10 films globally in 2024 were IP-driven, with two based on Japanese material (Sonic the Hedgehog and Godzilla Minus One). In the current year, Demon Slayer stands out as the fifth-highest earning film worldwide.

Using third-party data, Fujimura argues too that global rankings of fandom and the popularity of entertainment franchises place One Piece and The Elder Scrolls higher than Harry Potter or Barbie. And Japan’s Elden Ring and Grand Theft Auto rank above DC Comics and Star Trek.

All three pillars of Japanese entertainment are growing, with manga, revived by COVID-era lockdowns and a shift to digital distribution, surprisingly, the fastest expanding. It is projected to reach US$42 billion of revenue by 2030.

Anime (see page 22) is projected to reach US$60 billion of annual worldwide revenue by 2030, as it transitions to become what Fujimura calls a “global product” in an “era of borderless entertainment”.

And while game-to-film adaptations remain controversial among fans, the success of Japanese IP in this sector is significant.

Nintendo’s (animated) The Super Mario Bros Movie is heading to a second movie version. More Sonic the Hedgehog (live-action) features are in the pipeline. And Zelda, an Arad-produced live-action adaptation of Nintendo and Capcom’s The Legend of Zelda, is set as a major release for Sony Pictures in 2027.

Manga remains a reliable source IP. It is the origin of Amazon Studios’ series project The Promised Neverland; of Netflix’s Death Note; and Claymore for CBS Studios/Propagate.

Japanese and U.S. firms are now operating together to mine more forms of Japanese IP for further large-scale movies. These include: toys (Beyblade); graphic novels (Edge of Tomorrow); characters (Hello Kitty) and movie remakes (A Colt Is My Passport).

Fujimura says he counts 63 Japanese-sourced projects in development or production in Hollywood and “probably hundreds more”. But he acknowledges that many may fail to get to the start line.

Critical observers point to the sclerotic system of production committees, or risk-averse partnerships, that have long slowed decision-making in Japanese entertainment and hampered cross-border transactions; piracy, especially in the manga sector; and archaic working practices in Japan’s manga and anime sectors, where artists are aging, underpaid and not being fully replaced by younger generations of creators.

Japan’s slow-moving production structures may be out of touch with fan demand, while also leaving the sector open to piracy and challenges from other countries and systems, notably artificial intelligence (AI).

In October, the Association of Japanese Animations finally issued an open letter calling on the Japanese government to clarify its IP laws and for AI companies to stop infringing on copyrighted Japanese content – or at least to be transparent about the materials they use to train their generative AI models – and to pay for usage.

While the numerous obstacles may mean that Japanese IP never reaches Fujimura’s lofty predictions, few analysts these days doubt that Japan’s potential is there.

And more investors are willing to take a punt on entertainment as Japan’s industry of the future. According to recent calculations by the Nikkei business newspaper, the value of Japan’s nine leading entertainment companies recently overtook that of the country’s leading automakers.

- By Patrick Frater